This post focuses on the work of Fink and Kahneman. The objective is to explore how bias can affect the framing of critical and complex leadership challenges, often resulting in intense pressure for decision-making.

Are Kahneman and Fink both relevant to Crisis Leadership?

Both Kahneman’s research on cognitive biases and decision-making (Kahneman, 2011) and Fink’s framework for crisis management (Fink, 2002) are well-known in their respective fields. However, they are typically discussed separately in different contexts.

It could be beneficial to connect Kahneman’s findings on decision-making and Fink’s phases of crises to gain an exceptional viewpoint on how mental shortcuts and biases affect crisis management strategies and at what stage of a crisis. Integrating these ideas could provide valuable insights into how decision-makers can successfully navigate and tackle crises. Despite being an unusual pairing, it presents an opportunity for a unique and insightful discussion.

For Better or Worse, for Richer or Poorer – the meaning of Crisis

Firstly, my attention is on any situation that can be considered as a crisis. This may not always be a natural disaster or a catastrophic event. It could also encompass scenarios such as corporate failures that damage their reputation, financial crises that result in a shutdown, or diplomatic crises that arise from armed conflicts or the possibility of such.

Fink probed the definition of a crisis and found it interesting that it aligns with its original meaning. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), a crisis represents a turning point that can lead to either a positive or negative outcome. The OED’s definition of crisis dates back to 1588.

A state of affairs in which a decisive change for better or worse is imminent; a turning point.

It is often said that there is an opportunity for growth during a crisis. However, the first step for a leader is to assess the situation and determine at what stage the event is currently in. This is where Finks also guides us to think about a crisis in the same way as we would for a disease, and, as we all know, this is how the COVID-19 pandemic played out. Each phase of a crisis, just as each stage of a disease, represents a different level of salience in terms of its prominence.

From Stages to Salience

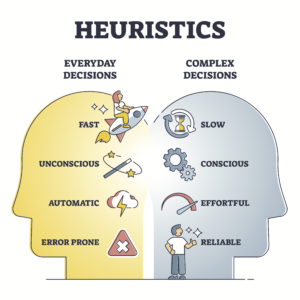

In leadership situations, it is essential to differentiate between quick thinking, slow thinking, and rational and ethical decisions. This is especially important when dealing with “wicked problems” that require operational actions. The ability to distinguish between these types of thinking is crucial when facing crises, whether emergent or actual. These crises could be related to public safety, such as disasters and atrocities, or corporate crises, such as cybersecurity, corporate reputation, financial crises, and diplomatic crises.

Many major crises throughout history, including the run on US Bank, the Northern Rock crisis in the UK, the Three Mile Island disaster, and others, could have been prevented if leaders had taken into account the “triggers” that existed during the Prodromal Phase, also known as the “pre-crisis” phase, somewhat inaccurately, according to Finks. Once the crisis reaches the Acute phase, it becomes impossible to reverse the damage, and the focus shifts to managing the consequences. A defining feature of a crisis is groupthink, which can lead to a no-turning point. Consequential leadership involves recognising these triggers and taking action as soon as they emerge to reach the turning point. In contrast, thinking slowly can help recover and rebuild as part of the Chronic Phase. This is where Kahneman’s work comes in.

Mastering Crisis: The Fast and Slow Approach in Crisis Phases

In “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” Kahneman delves into the two modes of thinking:

• System 1, which is fast, instinctive, and emotional, and

• System 2, which is slower, more deliberative, and logical.

During major crises, we rely on various systems to make decisions. Steven Finks has identified four phases of crises: prodrome, acute, chronic, and resolution. Each phase involves different cognitive processes, which require different approaches to “thinking”. The work of Kahneman supports decision-making in such crisis scenarios.

I will briefly outline how Fink and Kahneman could have easily collaborated in providing comprehensive and practical guidance to leaders when making decisions under pressure. In my Sunday ROAST, I will focus more on the practical aspects and the tools and techniques to guide leaders in their decision-making.

Phase 1: Prodrome Phase

During a crisis, individuals tend to rely on quick judgments and intuition, which is similar to System 1 thinking. However, engaging in System 2 thinking and critically evaluating the situation and its potential implications is essential. Ignoring triggers can lead to catastrophic consequences, so leaders should be vigilant and look out for them.

In this phase, it is crucial to acknowledge any biases and heuristics that might result in flawed judgments. By doing this, decision-makers can take a step back, gather more information, and analyse the situation more thoroughly. Kahneman’s work highlights the significance of this critical evaluation in making informed and effective decisions.

When a crisis approaches and moves from the early warning signs to a more critical stage, it becomes imperative to adopt System 2 thinking, which involves a slower and more analytical approach. This kind of thinking can be beneficial during the early stages of a crisis, providing more time to assess the situation and determine the best course of action. Ultimately, this can save lives and minimise the financial impact of the crisis.

Phase 2: Acute Phase

When the situation becomes more intense during a crisis, we often need to make quick decisions. At such times, we rely on our automatic thinking, known as System 1. However, it is essential to be careful and avoid impulsive reactions. Even in critical challenges that demand quick thinking, it is essential to engage in System 2 thinking, which involves analysing risks, considering alternative courses of action, and making better-informed decisions.

Ron Heifets’s seven principles of adaptive leadership provide valuable advice for such situations (Heifets, 1994). One of these principles involves “looking out from the balcony” while protecting and listening to the voices from below. This approach can help you create a holding environment that provides an immediate buffer between the fast and the slow to achieve the appropriate balance. Although creating such an environment may prove challenging, it is well worth the effort. Kahneman’s framework emphasises the need to slow down, resist the pressure for immediate action, and engage in deliberate, analytical thinking to mitigate the crisis’s impact effectively.

Phase 3: Chronic Phase

Decision-makers may face ongoing challenges and uncertainties during a crisis. As the crisis persists, it can become chronic and have a lingering impact. While relying solely on System 1 thinking could lead to fatigue, stress, and emotional responses, utilising System 2 thinking can help decision-makers maintain focus, adapt strategies, and manage resources effectively.

Kahneman’s insights into cognitive biases and the limitations of intuition can assist decision-makers in staying alert against complacency and overconfidence. This understanding promotes ongoing evaluation, the adaptation of crisis management approaches, and a dedication to creating learning organisations.

Phase 4: Resolution Phase

Now that the crisis has been resolved, it is time to focus on recovery and rebuilding. We often heard the phrase “Building Back Better” during the pandemic. Although people may be eager to put the crisis behind them, reflecting on what happened and learning from the experience is essential. This is a point that Fink made. If he had the chance to discuss this with Kahneman, they would agree. Both types of thinking can help implement measures that prevent future crises. Kahneman emphasises the significance of hindsight analysis, recognising mistakes, and incorporating feedback to make the organisation more resilient and better prepared for future crises. Steven Fink has made similar points in his work.

The Foundation of a Powerful Crisis Response Synergy

Combining Fink’s structured approach towards resilience with Kahneman’s agile decision-making insights can help organisations capitalise on crises. Developing leadership skills that enable decision-making at crucial moments can help leaders become more confident and influential. A true leader is known for their ability to make tough decisions. Fink’s crisis management framework provides the structure, while Daniel Kahneman’s insights into human cognition provide the necessary tools through agency.

Steven Fink’s framework offers a structured approach to comprehending and handling crises. It outlines the different phases of a crisis and guides how to navigate each stage proficiently. Fink’s work mainly concentrates on designing and arranging crisis management strategies, highlighting the significance of readiness, response, and recovery efforts.

Daniel Kahneman’s research focuses on the cognitive processes that underlie decision-making. He examines how people perceive and interpret information, make judgments, and choose courses of action. Kahneman aims to understand the active mental processes that influence our decisions, including the biases and heuristics that affect our thinking.

Fink and Kahneman’s work is crucial for comprehending and managing crises efficiently. Fink’s research emphasises the structure and procedures of crisis management, whereas Kahneman’s work explores the cognitive mechanisms that influence decision-making within those processes. Although both perspectives offer valuable insights, they focus differently: Fink concentrates on form, while Kahneman analyses agency.

Conclusion

Effective leadership demands the ability to think quickly in high-pressure situations and more deliberately and critically when necessary. Leaders who are open to learning from others and developing these skills are better equipped to navigate complex decisions in various sectors, lead their teams to success, and achieve their goals. This behaviour is crucial when lives and financial stability are at risk and the stakes are high. In some scenarios, poor decision-making can be catastrophic, resulting in significant loss of life or even financial ruin.

The right approach to thinking (fast or slow) can aid decision-making during crises by encouraging a balance between intuitive and analytical thinking, recognising cognitive biases, and promoting a systematic approach to problem-solving and decision-making.

It is essential to lead decisively and with a sense of purpose.

REFERENCES

Fink, S. (2002). Crisis management: planning for the inevitable.

Heifets, R. A. (1994). Leadership without easy answers. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow, New York, Farrar. Farrar.

Leave a Reply